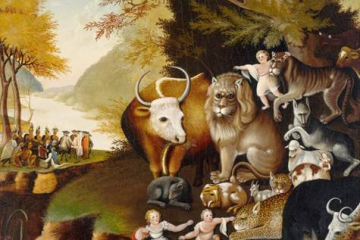

I shared this painting with you on Sunday. It is titled ‘David and Uriah’ and was painted c.1666-1669 by the Dutch master, Rembrandt. It captures the traumatic moment in 2 Samuel 11:14 when David signs Uriah’s death warrant and sends it to his general Joab “by the hand of Uriah.”

The painting was first given its title by Dr. Abraham Bredius (1855-1946), a Dutch art collector, art historian, and museum curator, and this has been supported by a number of other scholars from 1950 onwards.

The painting however is owned by the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Russia, where it bears the title, that it possessed when it entered the Russian imperial collection in 1773, ‘Haman Recognises his Fate’, from the story of Esther.

It is fascinating to think that, at some stage, people looked at this painting and saw King Ahasuerus, rather than King David; Mordecai rather than the prophet Nathan; and, most of all, the cruel and scheming Haman in the central character – rather than the innocent Uriah, being sent unknowingly to death by the king he served so faithfully. Fascinating that people could not tell the difference between the face of an evil man and a good man.

Perhaps this tells us how incrementally we can separate ourselves – as David does in the story (making war each Spring because it has become “the way of things”, distancing himself from the reality of conflict by staying in Jerusalem, sitting high in his cedar house above his subjects) – from others and from community and how slowly and steadily this separation can change us. How staying apart from others can start to cloud our moral judgment. How insulating ourselves from others can make us self-focused and self-obsessed. How distance from others can make us dismissive of human suffering (as David says in 2 Samuel 11:25, “Do not let this matter [Uriah’s death] trouble you, for the sword devours now one and now another…”).

And yet if this separation is a process that happens incrementally, perhaps there are small, incremental actions we can take, convictions we can cling to, God’s help we can ask for, that will reverse this corrosion of our hearts?

When the Women’s Book Group were away at the Benedictine Abbey in Jamberoo we read a little of Benedictine nun and theologian, Joan Chittister’s, Wisdom Distilled from the Daily. In one chapter, ‘The Way of Conversion’, she speaks about the importance of the “Instruments of Good Works” as identified by St Benedict.

These are, she says, firstly – the spiritual and corporeal works of mercy. “The spiritual life,” she writes, “is not a matter of not doing evil to the other; the real spiritual life depends on our doing good for the other.”

The second category, she says, of the “Instruments of Good Works” are about being good community and family members. “For the Benedictine, life in community is the great human asceticism. To live community life well is to have all the edges rubbed off, all the rough parts made smooth…”

The third category deals with personal maturity and spiritual growth. Here we are told to, “live life with seriousness of purpose and a consciousness of ultimate things, to reach out to others, to love… and, finally, when we fail and fail and fail in all of these, never to despair.”

Are those three categories helpful for us? Are we able to – to reword Micah 6:8 slightly – do mercy, love community (even when it’s tough) and walk humbly with our God who loves us?

Grace and peace to you – embraced by that love – this week.

Belinda