Our Great High Priest – Isaiah 53:4-6, Hebrews 5:1-10

In The Silver Chair, part of the Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis, there is an section I often think about: the confrontation, deep underground, between the Witch and Jill, Eustace, Puddleglum (who could forget the Marsh-wiggle!) and Prince Rilian. Rilian has just been freed, but the Witch returns to enchant them, to convince them all they know of the world is just dreams. That Narnia is a dream. That the sun is a dream, that they have imagined something bigger and better than a lamp and called it the sun. That Aslan, the great lion, is a dream, that they have imagined something bigger and better than a cat and called it a lion.

But then, Puddleglum stamps the fire out with his bare feet and says to the Witch: One word, Ma’am…. All you’ve been saying is quite right, I shouldn’t wonder…. But there’s one thing more to be said, even so. Suppose we have only dreamed, or made up, all those things – trees and grass and sun and moon and stars and Aslan himself. Suppose we have. Then all I can say is that, in that case, the made-up things seem a good deal more important than the real ones. Suppose this black pit of a kingdom of yours is the only world. Well, it strikes me as a pretty poor one…. I’m on Aslan’s side even if there isn’t any Aslan to lead it. I’m going to live as like a Narnian as I can even if there isn’t any Narnia.

There’s a parallel to this in our reading from Hebrews this morning where the writer of Hebrews compares the role of the high priest in the Aaronic tradition with that of Jesus, who is called in chapter 4, verse 14, our “great high priest”. The former is more concrete, more visible, known throughout the Mediterranean world, and the latter is far less tangible, only spoken of, only experienced, among a small group of persecuted early believers. And yet, according to the writer of Hebrews, to borrow the words of Puddleglum, the high priesthood of Jesus licks the apparently ‘real’ one hollow; for Jesus, verse nine, has become the actual “source of eternal salvation for all who obey him.”

And in these ten verses the writer of Hebrews lays out the reasons why.

Firstly, every high priest must be called by God, appointed by God. The Aaronic priesthood – as the name indicates – traced their election back through their lineage to Aaron, the brother of Moses, the first high priest. As it says in Exodus 28:1 and 43, “Aaron, and his sons with him… [will] serve me as priests…. This shall be a perpetual ordinance for him and for his descendants after him.”

The point of being appointed by God, however, is that it confirms you are an effective intermediary for the people; that God will listen to you. As verse one says, “every high priest…is put in charge of things pertaining to God on [the people’s] behalf, to offer gifts and sacrifices for sins.” And what the writer goes on to say is that God will listen to Jesus because Jesus’ claim does not come through a long line of ancestors but is a direct claim and a deeper claim, and as evidence two psalms are quoted; Psalm 2 where God says, “You are my son,” – ‘my son’ – the same words spoken at Jesus’ baptism – in the biblical tradition you cannot get any more direct communication than that, and Psalm 110, which says, “You are a priest forever, according to the order of Melchizedek.”

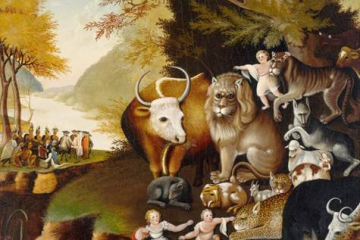

To understand this second reference, we need to look at small story in amongst the legends of the Jewish patriarch, Abraham; Genesis, chapter 14, where Abraham meets Melchizedek, the king of Salem, also known as, the priest of God Most High. It is a time of great unrest. (I was made to watch The Hobbit trilogy again during lockdown, but this is not just the battle of the five armies, but the nine armies – four kings versing five!) And in the aftermath of the fighting, in the looting and pillaging, Abraham’s nephew, Lot, and all he owns is taken, and Abraham goes after him, defeats the victorious kings, and brings back Lot and his household and everyone and everything else. And then he is met by a king who hasn’t been mentioned previously, who, apart from Psalm 110, is never mentioned again till the book of Hebrews, a king – priest who comes bearing bread and wine, whose name, Melchizedek, means ‘King of righteousness’, whose kingdom, Salem, means ‘Peace’, and who comes with God’s blessing.

This is the priesthood of Jesus, the writer of Hebrews is saying, one that is righteous, one that brings peace, one that is directly appointed by God – not through family connections, one that goes back further and deeper into God’s plans for humanity and reaches wider than the exclusive Aaronic priesthood to bless and to intercede for all people. This is our high priest – one who is indissolubly linked to God and God will listen to him.

Secondly, all high priests are appointed, verse 2, to “deal gently with the ignorant and wayward,” because they themselves are, “subject to weakness”. Jesus does not offer sacrifice for his own sins, as other priests must do – Jesus was without sin (chapter 4, verse 15) – but he was human just as we are, weak just as we are, tested just as we are. Therefore, he can sympathise fully with our weaknesses, and articulate fully our suffering.

In verse 7 the writer says, “in the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears…” It is a reference his suffering in Gethsemane, his experiencing the worst human beings can do to each other, but it also reveals the power of the incarnation. As our Isaiah reading said, the servant of God, “was wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities.” Jesus’ willingness to suffer with, to suffer for, human beings reveals the depth of his love for us, the depth of his understanding of our human condition.

William Barclay quotes a rabbinic proverb here, “There are three kinds of prayers, each loftier than the preceding – prayer, crying and tears. Prayer is made in silence; crying with a raised voice; but tears over come all things.” Jesus wept for his friends, for the grief and suffering they experienced, and Jesus, as our high priest, weeps for us.

There is a scene in the TV series, The West Wing (we were just commenting the other day, James, how well it still stands up!) where White House Chief of Staff, Leo McGarry, tells Josh Lynam, who has just acknowledged he is suffering post-traumatic stress, a story. There are Christmas trees in the background, which is not an accident, because this is a story about the power of the incarnation, and it speaks into what we are talking about during Mental Health Month as well.

“There’s a guy walking down a street,” Leo says, “when he falls in a hole. The walls are so steep, he can’t get out. A doctor passes by, and the guy shouts up, ‘Hey you, can you help me out?’ The doctor writes a prescription, throws it down in the hole and moves on. Then a priest comes along, and the guy shouts up, ‘Father, I’m down in this hole, can you help me out?’ The priest writes out a prayer, throws it down in the hole and moves on. Then a friend walks by. ‘Hey, Joe, it’s me, can you help me out?’ And the friend jumps in the hole. Our guy says, ‘Are you stupid? Now we’re both down here.’ The friend says, ‘Yeah, but I’ve been down here before, and I know the way out.’”

I can think of so many examples of members of this congregation – just this week – helping each out like this. Those who have experienced mental illness helping others with mental illness. Those who have been diagnosed with cancer helping others with cancer. Those who have lost people they love helping others who are grieving. Those who have struggled to find work or had a difficult time at work helping others who are having a hard time.

Jesus our great high priest, the text says, suffers with us, prays for us, but also through his suffering learns obedience, opening for us the way through death to eternal salvation.

We struggle with this word ‘obedience’. For us it is associated with someone giving orders to someone else; with that someone else having to do things they do not want to do. But the “reverent submission” that is spoken of here is something else entirely. The word obedience comes from the Latin ‘ob-audire’ which means ‘to hear, to listen well’. Just as Jesus prays well, offering up heart-felt “prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears”, so Jesus listens well, hearing God’s loving word and responding to it. Henri Nouwen writes, “Obedience, as it is embodied by Jesus Christ… is an expression of the intimacy that can exist between two persons. Here the one who obeys knows without restriction the will of the one who commands and has only one all-embracing desire: to live out that will.”

Jesus lived out the will of God. He embodied the love of God for human beings. As Philippians 2:7 says, “Being born in human likeness, and being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death – even death on a cross.” Jesus jumped down into the hole with us – to be with us – and having lived out in every way the love of God – showed us the way out. He became, as verse 9 says, “the source of eternal salvation for all who [in their turn] obey [who listen well, who live out the will of God, who love] him.”

I rang someone in the church this week who answered their phone and said, “Oh, Belinda, ‘What a friend we have in Jesus!’ I knew it was you.” They have, apparently, chosen that as their ‘Belinda-specific’ ringtone.

But that perhaps is the point! What a friend we have in Jesus! What a high priest we have in Jesus! One who God will listen to, one who knows our deepest pain, our most heart-felt prayers, one who listens to God and walks to the path of peace even when it takes them through suffering.

And we, too, through this high priest now have a direct connection to God; we are God’s sons and daughters! God listens to us, God knows our pains and hears our prayers, for ourselves and others, and God calls us to listen well, to listen in love, as we, in our service, in our suffering, in our perseverance live out God’s will for our world.