I mentioned two weeks ago that we were moving away from the Old Testament kings, but we have not moved very far! We have, however, changed genres and for the next three weeks we will be examining the wisdom literature of the Old Testament – writing that focuses less on the story of Israel and God’s redemption, and more on universal questions of why suffering and inequality and death exist, how a good life is to be lived, and expressing joy in creation and God as the Creator.

Wisdom literature is found throughout the Old Testament, but four books are dedicated to it: Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and the Song of Songs – also called the Song of Solomon because the superscription (the inscription above the text) reads, “the Song of Songs, which is Solomon’s”.

Solomon, as we know, was famous for his wisdom, and is thought of as the founder of Israel’s wisdom tradition, but although Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and the Song of Songs – the three books we will be looking at – are attributed to him, all three show evidence of having been compiled over many centuries. A charming legend in the Talmud, however, says that Solomon wrote the Song of Songs in his lusty youth, Proverbs in his mature middle age and the sceptical Ecclesiastes as an old man, so as nod to the legend, we will address the three books over the next three weeks in that order!

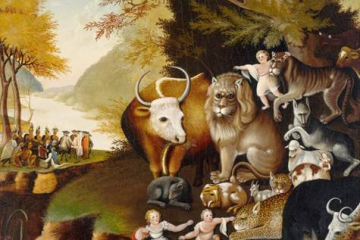

So today we are looking the Song of Songs – and the images come from Marc Chagall’s Song of Songs series, painted between 1957 and 1966. The expression ‘song of songs’ in Hebrew means that something is the greatest and most beautiful of all in its class (like the expression Holy of Holies).

But if you have ever read the Song of Songs, you might be asking – what in the name of all that is holy – is this doing in the Bible? What does this collection of erotic love poetry have to do with holiness?

This morning, I want to broaden that question and ask what does erotic love poetry or feminism or the documentaries of David Attenborough have to do with holiness?

But, to get us started, I thought I would ask some of the more senior couples in our congregation what it was that first attracted them to their partner?

Interviews with Gary and Helen Hilton, David and Helen Stafford…

Did you hear any echoes of, “My beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag…on the mountains?” Or “O my dove… your voice is sweet, and your face is lovely?”

What I hear in the descriptions we heard this morning, and the descriptions of love in this text, the way the lovers describe one another, is people paying close attention – becoming attentive – to one another. This is what falling in love is like – whether it is a romantic relationship, or someone caring for a newborn marvelling at their tiny perfect fingers and tiny perfect feet, or some area of life or activity about which you are deeply passionate. Get twitchers or train spotters talking about you will quickly discover this! When we fall in love, we become attentive to the beloved.

And this attentiveness, in the Song of Songs, is a lasting attentiveness. The two lovers remain faithful, despite the obstacles they face, to one another. “My beloved is mine and I am his” (2:16) or, “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine” (6:3) Or in 8:11, the woman says, “My vineyard, my very own, is for myself; you, O Solomon, may have the thousand…”

And in this attentiveness, there is also mutuality. Each of the lovers bring their all to this relationship. And the woman is not the lesser party or the less empowered party here, but in fact speaks more often than the man. There is attentiveness to the female voice in this text affirming that female voices can offer wisdom and theological value.

Feminist scholars point to the Song of Songs as a reversal of the punishment given to Eve in Genesis. In Genesis 3:16 it says, “Your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.” But here, in Song of Songs 7:10, the woman says, “I am my beloved’s, and his desire is for me.” This word ‘desire’ is a rare word in the Hebrew Bible, appearing only three times, twice in Genesis in the context of sin and the fall, and here, as a promise of restoration between the woman and the man, and restoration of mutuality in relationships.

The Songs of Songs then is a glimpse of God’s promise of shalom of peace and wholeness and fullness of life.

There is another form of attentiveness in this text. It is, perhaps more than any of biblical text, filled with descriptions of the natural world, which is why I liken it to a David Attenborough documentary. There are plentiful vineyards (1:6 and 14, 2:15, 6:11, 7:12, 8:11-12), rich pastures (1:7-8, 2:16, 4:1 and 5, 6:3 and 5, 7:11), fruitful orchards and lush gardens (4:12-5:1, 6:2 and 11, 8:5 and 13). Twenty-four plant varieties are specifically named, from henna blossoms to cedars, from wildflowers to exotic spices like myrrh.

Elaine T James of Princeton Theological Seminary, writes that the Song contains a “detailed description of the natural world, including climatological factors, attention to season and agricultural practices, the observation of blossoms and fruiting trees and of course the vineyard.” These are potent symbols of sensuality and sexuality, but they are also signs of attentiveness to the world around us, an attentiveness that is being lost and lost “faster in wealthier western nations than anywhere else in the world.” As James comments, “the Song models an ethical stance: to see the lover as a landscape. And again: to see the landscape as a lover. How could our ethics of [the natural world] be shaped by taking seriously this radical vision?”

The Song of Songs, as I’ve said, is a glimpse and a call to us also to pay attention to God’s promise of peace and wholeness and fullness of life.

There is another word for this practice of attentiveness and that word is reverence.

“The easiest practice of reverence I know,” Episcopal priest and author, Barbara Brown Taylor writes, “is simply to sit down somewhere outside, preferably near a body of water, and pay attention for at least twenty minutes. It is not necessary to take on the whole world at first. Just take the three square feet of earth on which you are sitting, paying close attention to everything that lives within that small estate….

With any luck, you will soon be able to see the soul in pebbles, ants, small mounds of moss, and the acorn on its way to becoming an oak tree. You may feel some tenderness for the struggling mayfly the ants are carrying away. If you can see the water, you may take time to wonder where it comes from and where it is going. You may even feel the beating of your own heart….

If someone walks by or speaks to you, you may find that your power of attentiveness extends to this person as well. Even if you do not know him, you may be able to see his soul too, the one he thinks he has so carefully covered up.”

If you have read anything about the Song of Songs you will know that first the Jewish rabbis and then the Christian church rationalised its inclusion in Scripture as a description and celebration of the love between God and Israel, or God and the Church, an extension of the metaphor of marriage found in several biblical books. For me, however, it is the quality of attentiveness to the other and the world around us in this book, the practice of reverence for others and for creation in this book, the glimpse of God’s promise of shalom in this book that speaks, so powerfully and hopefully and wonderfully, of God’s faithful and whole-hearted love for us – and – and this is the most wonderful thing – our faithful and wholehearted love for God. The Jewish scholar and mystic, Rabbi Akiba, wrote, “The whole world is not worth the day on which the Song of Songs was given to Israel, for all the Scriptures are holy, but the Song of Songs is the Holy of Holies.” (Mishnah Yadayim 3:5)

Composer David Lang was also drawn to the quality of attentiveness in the text of Song of Songs. In 2014 he composed a song Just (After Song of Songs) in which he took the two main voices, a man and a woman, and listed everything each individual owns within the Song of Songs. To differentiate between the two voices, because his composition is sung by three women, the statements of male ownership are introduced with, ‘just your [blank]’, and the statements of female ownership with, ‘and my [blank]’. The rare instances of shared ownership he writes as ‘our [blank]’.

He explains, “One thing that has always interested me about the text is that the man and the woman in the Song of Songs have attributes, they notice things about each other, they own things, they have features that are desirable. In a love between people this would be no surprise. In a love between Man and God, however, that might mean that in this text are clues to the nature of God’s own attributes, and a record of how they might attract us…. The Song of Songs is a metaphor for our passion for the Eternal.”

The Songs of Song is a metaphor and a passionate rallying cry for us to pay attention to one another, to our world and to our Eternal Creator.

Can I invite you now to listen to part of David Lang’s Just (After Song of Songs) and use it as your response – your prayer – saying to God what you notice – what you are attentive to in God – and listening for what it is that God is attentive to in you.

Prayer of Thanksgiving

God of all blessings,

source of all life,

giver of all grace:

We thank you for the gift of life:

for the breath that sustains life,

for the food of this earth that nurtures life,

for the love of family and friends

without which there would be no life.

We thank you for the mystery of creation:

for the beauty that the eye can see,

for the joy that the ear may hear,

for the unknown

that we cannot behold filling the universe with wonder.

We thank you for setting us in communities:

for families who nurture our becoming,

for friends who love us by choice,

for companions at work, who share our burdens and daily tasks,

for strangers who welcome us into their midst,

for people from other lands who call us to grow in understanding,

for children who lighten our moments with delight,

for the unborn, who offer us hope and a challenge for the future.

We thank you for this day:

for life – and one more day to work for justice and peace and life for others,

for opportunity – and one more day to care for those who are sick or distressed (we pray for Richard and Judith, for Dorothy and Siriphan and others now),

for neighbours – and one more person to love and by whom be loved,

for your grace – and one more experience of your presence,

for your promise: to be with us, to be our God,

to bring shalom and salvation.

For these, and all blessings,

we give you thanks, eternal, loving God,

through Jesus Christ we pray. Amen.

~ adapted from “Prayers of Our Hearts” © 1991 Vienna Cobb Anderson. Posted on BeliefNet.com