Over the last two weeks I have been imagining – like this story we read in Luke imagines – or the jokes we tell about people arriving at the Pearly Gates to meet St Peter imagine – the Queen arriving in heaven alongside someone who has led a very ordinary life, or someone who has been desperately poor all their life, and receiving – despite the vast disparity in ceremony with which they left the world – an identical welcome! And in my imagination, the Queen, as a person of faith, is completely at peace with this – for at last she sees, face to face, the one she has loved and served all her life.

This story in my imagination is not the story that Jesus tells here.

In his story a rich man and a poor man reach heaven and discover that a vast gulf – a great chasm – separates them.

At first it appears to be a story about reversals of fortune.

The rich man has no name, and the poor man is named Lazarus. (Even this – that the poor have names, and the rich are anonymous – is a reversal of fortune, though Jesus is likely building here on known folklore, rabbinic stories, about Eliezer, Abraham’s servant, who was said to wander the earth reporting to Abraham how his children were observing the Torah regarding the treatment of widows, orphans, and the poor.)

The rich man, in the story, goes from riches to agony, and the poor man goes from rags (and agony) to blessing. The sumptuous feasting of the rich man in life contrast sharply with his unquenchable thirst after death; and the horrific conditions of Lazarus in life, “even the dogs would come and lick his sores”, contrast with his honoured position in death resting in Abraham’s bosom. It is an image that has comforted many who have lived lives of terrible suffering, and it inspired the Afro-American spiritual we sang part of earlier:

Rock my soul in the bosom of Abraham…

But the story does not exactly depict reversals of fortune.

After all Lazarus, who was poor, is not showered with riches after death. Instead, he is brought to a place of honour, and great intimacy – reclining against Abraham’s breast or bosom (an image of physical proximity we in the West find uncomfortable, so it has been translated ‘with’ or ‘beside’ in the NRSV). He is not showered with wealth, but showered with affection; with the care, the caring attention, the relationship that he was denied in life – despite his physical proximity then, laying at the rich man’s gate.

The rich man also doesn’t undergo the kind of reversal we might expect. Even in death he clings to the power, the sense of entitlement, he had in life. “Father Abraham,” he calls out, implying he and Abraham have a close relationship, one with obligations. “Send Lazarus to help me.” When Abraham points out that a great chasm lies between them, that it cannot be crossed, the rich man says, “Send him then to warn my siblings…” Lazarus, in his eyes, remains an inferior to be ordered about.

My mother tells a story of working in the pharmacy in Lae, PNG, in the late 60’s and a wealthy man, whose family have featured in ABC documentaries, coming in for medical supplies. After paying he simply walked away from the counter. “Sorry, you’ve forgotten your box!” she called after him. “It’s your boy’s job to put it in the car,” he said, indicating the local Papua New Guinean man also serving at the counter. Incensed, mum picked up the box, marched past him and put it in the car herself.

What the story describes is a great chasm – one that cannot be crossed be crossed in death – but can easily be crossed in life – if people are prepared to do so. It is a story then, not of reversal of fortunes, but of a missed opportunity for renewal of relationship.

Two months ago, some of the deacons, Steve and myself did a mini road trip visiting different community programs in this region, and to aid our thinking and reflecting, we read an article by Jon Kuhrt from West London Mission in which he identifies three forms of poverty. Material poverty is one most obvious to us, he said, but there is also relational poverty, the absence of positive relationships with others, and poverty of identity, the loss of an essential healthy relationship with yourself, inner well-being.

He tells the story of Trevor, who had come out of prison and had multiple addictions, crack, heroin and alcohol, whose house people from his church went to fix up. To their genuine surprise, Trevor then started coming regularly to church. He would often interrupt the service with long monologues about how nobody cared for him, and he would then be escorted out of the building, as they made it clear that there were boundaries and interrupting services was not acceptable. He would often then leave and come back afterwards for coffee. They found out that he had been banned from every local community centre – only their church and the local pub maintained a relationship with him.

Knowing Trevor, Kuhrt says, not as a ‘client’ but as a neighbour, fellow church goer and, in some ways, as a friend, was unsettling, but it taught him far more about poverty – that it has all these three dimensions; material and relational and personal.

A few years later Trevor became unwell, and spent more and more time in hospital, but would often discharge himself to come to church. At his funeral his sister paid a moving tribute to the difference the church had played in his life – not to do with meeting his material needs but by meeting his relational needs and his need for identity.

Kuhrt writes, “The church can do a huge amount to respond to poverty – both practically…and politically…. All these things are essential – but [we] should not limit ourselves to responding materially…. For the gospel of Christ offers unique resources to address the poverties of relationships and identity…. The heart of the message… is the offer of a new relationship – both within a church community but also, more importantly with God…. a relational God…who reaches out to us with love and reconciliation.”

We love and serve a relational God, a God of reconciliation, who has done everything Abraham said was impossible, who has breached the great chasm between God and sin, who has fulfilled the message of Moses and the prophets, who has risen from the dead, in order to restore relationship with us – to draw us into God’s bosom – and to draw us into relationship with all others.

But what if there are some situations to which we can only respond materially?

I am not if that is ever entirely the case, and what has helped me to think this has been meeting, as part of the Micah Women Leader’s Delegation, Kirsty Roberston. Kirsty and I worked, at different times, for the same organisation, Force Ten, a joint programme of the National Council of Churches and Caritas Australia, or Australian Catholic Relief, as it was then, and Kirsty is now the CEO of Caritas, and two months ago, she had the opportunity to travel to Ethiopia.

They wanted to visit villages that were far beyond the current extent of aid programmes, so after six or seven hours of driving they reached a village and all the men came out to speak to them. And at the end one of the women came forward, and she said to Kirsty, “Now you should hear from a woman!” And Kirsty liked her immediately.

This woman, whose name is Mali, invited Kirsty to come to her home, and she showed her – she was very proud of this – her door padlock. She explained she was a first wife, her husband now lived with his new wife, and that she was responsible for her eight children. The padlock allowed her to lock her door at night, giving them some security, when she went for water. Collecting water used to take an hour or two, but now, in their fifth year of drought, it took over a day. She had left the evening before, collected water, rested for a while, and only just returned now around midday.

Kirsty and Mali talked, through a translator, for around two hours. They talked about their families and Mali offered to show her how to grind grain. When Kirsty’s efforts were very ineffectual, Mali said it was good she had only one child to feed!

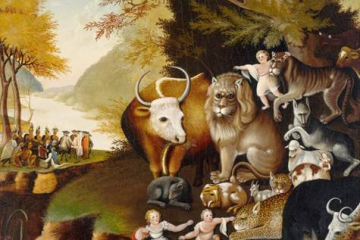

Kirsty said she really got to know the goat you can see in the picture. It kept butting and nudging her – probably because Mali had seated her in the only patch of shade. In good times Mali said she would have had around 20 goats, but they had died of hunger, or she had killed them to fed her children, and this was her last goat.

Kirsty asked if she could tell Mali’s story to others, and Mali said, please tell my story so people can help us. And that is what we were doing at Parliament House, telling Mali’s story, raising awareness of this famine brought about by climate change, by Covid disruption and by conflict, 40-90% of wheat imports to the Horn of Arica came from Ukraine.

So yes, we should respond to this poverty materially, but we can also respond relationally. We can remember Mali and others in her situation. We can pray for them. We can give. We can work to alleviate climate change and work to support agencies working on agricultural innovation, empowering women in agriculture and food systems, scaling up disaster risk reduction and supporting peacebuilding programmes. And we can advocate for them by writing letter – which we have an opportunity to do after today’s service.

These stories in Luke 16, as I mentioned last week, build on the words of the Magnificat from Luke 1; “He has brought down the power from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty…” But if I can disagree with what I preached last week – this is not turning the world upside down – but of bringing all people into a new place, a new place of relationship, of communion with one other, where the rich see the poor, like Mali (unlike the rich man who only saw Lazarus after death) and where the poor know the rich, as Trevor came to know those in his church, where we are able to meet each other’s needs; material, relational and personal; this place is where the love of God locates us. “Only in heaven,” said Mother Theresa, “will we understand how much we owe the poor for helping us to love God like we should.”

Let us, as an expression of our desire to love and serve God as we should by loving others, remind ourselves of God’s great love for us. Let’s sing together:

Rock my soul in the bosom of Abraham…