I came across an article this week titled, “Where we sit in church says a lot about us.”

The author comes clean. “I am”, he says, “a lifelong and perpetual Right Sider. I have tried now and then to sit with friends on the Left Side, but the experience left me with profound discomfort….” I am also, he says, “decidedly a Back Bencher. I have a favourite pew, about five rows from the back, and I like to sit on the aisle. I can defend this by reference to the teachings of Jesus, who urged the faithful not to show off their piety in the front. He preferred those who prayed humbly in the back.”

These are several reasons, he says, why right is right. The choir is on the right. And – in his church – the pulpit is also on the right so he can hear – better? – the scripture readings, sermon and prayers. The children, on the right, he thinks, are also slightly more rightly behaved. “I could,” he says, “make a case that we Right Siders are more interesting and better looking…. We [do] have — if laughter is evidence — a better sense of humour.”

“I know I am committing the sin of Pride, and that Pride cometh before the Fall. But the Fall is right around the corner, so…, once again, I am Right.”

My favourite church cartoonist, Dave Walker, has this take on, ‘What your pew says about you’, but I also like his suggestion that the perspective of the vicar might be very different to the perspective of the congregation!

As I read this terrible story about the actions of David; their impact on Bathsheba’s and Uriah’s lives; and the subsequent unravelling of David’s family – and for a time his kingdom – an expression came to mind, first coined by US government department head, Miles Rufus, “Where you stand depends upon where you sit.” In other words that how we see things and make judgments and act is shaped by our perspective; that we need to discipline ourselves to see things from another point of view.

This story is a perfect illustration of that principle and its remedy.

One disclaimer. This sermon, and this passage, does not really focus on the impact of this rape – because that is what this is (I have crossed out the heading in my Bible that says, “David commits adultery with Bathsheba” and written “David commits rape”) – on Bathsheba. We know only a little of Bathsheba’s story; that she grieved for her husband (verse 26), grieved for her son (12:24); that she was the mother of Solomon and helped secure the throne for him after David (1 Kings 1 and 2). So, it is coincidental, but fortuitous, that next week our speaker is Paul Flavel, Executive Director of Hagar Australia, an organisation that works with people affected by abuse and exploitation, trafficking and slavery. The work of justice for Bathsheba continues.

But what we see here is that where David stood, his view on the world, his judgements and actions were heavily impacted by where, as king, he chose to sit.

Firstly, verse 1, “In the spring of the year, the time when kings go out to battle, David sent Joab with his officers and all Israel with him; they ravaged the Ammonites, and besieged Rabbah. But David remained at Jerusalem.”

I was always told, in my Bible lessons growing up, that this verse was a critique of David; that David was not with his people as he was meant to be. But reading the passage again I feel the critique goes deeper. The Lord, we’re told in chapter 7, had given David rest all from his enemies. And there are multiple assurances in that chapter that God is in charge; that God will continue to give them rest. But here in chapter 11 David is continuing to make war because, as the prophet Samuel warned, “These will be the ways of the king…” War will become normative, routinised, marked on the calendar for each Spring.

And now David sends others to do the fighting for him. He directs this routinised violence from a comfortable distance. As Professor of Hebrew, Roger Nam says, “This is a very different portrayal of David from his battle with Goliath.”

Secondly, as we heard last week, David now has an impressive house of cedar, a house higher than other houses (verse 8), and from the roof of his house, a higher position again, he sees a woman bathing. He sends someone to ask who she is. She is the daughter of Eliam and wife of Uriah the Hittite – both names appear in the list of David’s greatest warriors in chapter 23. But despite discovering this, he sends messengers to get her. (The Hebrew is stronger; ‘to grasp her’ or ‘take her’. As I said, this is rape – not an adulterous affair.) Again, we hear Samuel saying, “These will be the ways of the king…he will take; he will take your sons; he will take your daughters.”

David, sitting physically above Jerusalem, sees himself as standing above the rules that govern other people, above the law. Where you stand, depends on where you sit.

But, suddenly, in verse five, with the message from Bathsheba that she is pregnant, David’s power and control over the lives of others starts to unravel.

He devises a plan. He asks Joab, his general, to give Uriah the Hittite rec leave. Surely Uriah will take the opportunity to come home and have sex with his wife! David even tells him to! Verse 8, “Go down to your house, and wash your feet.” (I am sure you have been around this church long enough to know feet are a euphemism!)

But Uriah sleeps, verse 9, “at the entrance of the kings house with all the servants of his lord.”

The next conversation is very revealing. “You have just come from a journey!” David says, “Why did you not go down to your house?” The NIV puts this, “Haven’t you just come from a military campaign?” I feel like David is questioning Uriah’s manhood, “What’s wrong with you, mate. Go home and sleep with your wife!”

And Uriah’s response is stunning. He says, “The ark and Israel and Judah remain in booths, and my lord Joab and the servants of my lord are camping in the open field; shall I then go to my house, to eat and to drink, and to lie with my wife?” And he swears on the life of David, “I will not do such a thing!”

The ark of God is still in a tent. The people of God still live in tents. My commanding officer and fellow soldiers are in tents. How is it possible that I can enjoy ease and pleasure when everyone I am responsible to, and everyone I am responsible for, does not? Uriah’s statement is an unconscious, but devastating critique of David.

But David is not done. He tries another masculine trope. I’ll get him drunk. Then he’ll go and do the deed. But even a drunk Uriah is a man with principles.

So, David sends a letter to Joab, telling Joab to put Uriah in the thick of the fighting, and to let him be killed, and sends the letter by the hand of Uriah.

The text sets up this incredible contrast between Uriah the Hittite, who despite being a foreigner, behaves with honour, who does not take up his normal rights as a husband out of solidarity with his people, and David, the so-called righteous Israelite king, who speaks the word shalom ‘peace’ three times in verse 7 while behaving deviously, who takes first Uriah’s wife and then Uriah’s life.

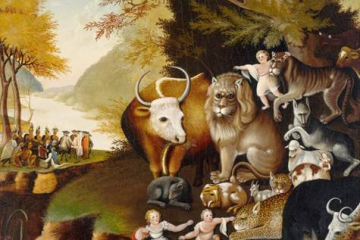

This painting by Rembrandt captures the moment where David sends Uriah back to Joab carrying the letter. David sits in the background, his face deliberately concealing that he has done, first rape and now murder. Also in the background is the prophet Nathan who is soon to condemn David for his actions. But the foreground figure, dressed in red, is Uriah, whose face, it seems to me, resembles that of an icon, an icon of a saint or perhaps an icon of Christ.

As Philippians 2 says:

“Let each of you look not to your own interests but to the interests of others. Let the same mind be in you that wasin Christ Jesus,

who, though he existed in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God as something to be grasped,

but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave, assuming human likeness.

And being found in appearance as a human,

he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.”

Uriah shows us something of the mind of Christ. Out of his love for his people, his care and compassion for his people, he is obedient to the point of death. Unlike David who allows where he sits to affect what he stands for, Uriah knows where he stands, and this determines where he sits.

Where do we stand? Where do we sit? Do the places we choose to sit in heighten our sense of superiority over others, of separation from others? Do we feel deserving of the comforts and pleasures we enjoy. Do we willingly ignore the impact our lifestyles may have on others? Or do we stand for justice for others, for equity in our world, for care for this planet? If we do, how will this change where we sit?

We sang in our last hymn, “Give us this day the bread of peace,

The hands to share a common good,

The hearts to ache for justice’s sake,

The will to stand where Jesu stood.”

Let us commit ourselves to that prayer as we sing our next hymn.