Isaiah 56:1, 6-8, John 12:20-33

Who got a chance to see the exhibition that has finished now at the Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture, Jesus, laughing and loving?

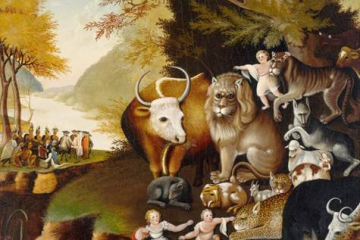

As the title says, the exhibition was intended to expand our perception of Jesus, to see him not only as sombre or stern or tortured and suffering, but also as light-hearted, as someone who was good company and who enjoyed the company of others. The exhibition also showed us pictures of Jesus with different faces; certainly different from the ones that adorned my Children’s Bible or Sunday School room walls; faces that remind us of Jesus’ words in John 12, “When I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw all people to myself.” And we know these different images of Jesus are powerful. Dinorah Nieves, a sociologist and author from Los Angeles says, “Multiethnic representations of religious symbols of all kinds are important to everybody, but particularly in [marginalised] communities. It’s important for us to see melanin and sacredness as connected and not opposites.” I love that line – ‘to see melanin and sacredness as connected and not opposites.’ The fulfilment of, ‘I will draw all people to myself’.

If you went (or saw the exhibition advertising) you will remember this picture – Jesus the labourer who looks like an ordinary Papua New Guinean painted by Mairi Karl Feeger. Or you might remember this, Jesus, washing the feet of his disciples, painted by Ketut Lasia in a classical Balinese style. Or – and this was my favourite – Emmaus; a reimagining of the Emmaus story by Filipino Emmanuel Garibay where those who share bread at the table are ordinary, perhaps even suspect, Filipino street people. As Garibay says of this work:

It is very difficult for most people to contextualise their faith because the colonial packaging… has been deeply embedded in their consciousness…. So the figure at the centre [of the painting] is a woman – she is drinking with them and telling a joke and everybody is laughing around her. But the real joke is that people are laughing because they thought all along that Jesus was a man, and that Jesus was a Caucasian-looking guy, you know…. I have a different image of Jesus, which is that of woman, a very ordinary-looking Filipino woman, who drinks with them and has stories to tell.

It is a long way from this, isn’t it! And yet, in the 1930s, students at McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago voted a black and white sketch of this image by illustrator Warner Sallman, the ‘most accurate portrayal of Jesus’. A publisher bought the rights and an industry was born. During World War II wallet sized versions were distributed to US troops and the image appeared everywhere on church bulletins, calendars, posters and bookmarks.

But I want to show you one final image – not from the exhibition – but referencing Sallman’s The head of Jesus by New Zealand artist Sofia Minson. It shows Jesus as a Maori man with full-face moko (traditional tattoo) and a huia bird, once native to New Zealand but now extinct, as a neck ornament.

All these wonderful multi-ethnic images of Jesus, all this powerful contextualisation of faith, is foreshadowed in our reading this morning, when some Greeks, also in Jerusalem for the Passover, come and say – in a culturally appropriate way (that seems round-about to us) by going first to Phillip and then through Andrew – they want to see Jesus. For Jesus this is the sign, the sign that the long-awaited gathering of the nations to Jerusalem, described in our Isaiah reading, has begun. What the writer of John wants us to note is that the prophecy is being fulfilled by these Gentiles coming – not to the temple – but to Jesus. “The hour has come,” says Jesus, “for the Son of Man to be glorified.”

But what does glorification mean for the Son of Man? “Very truly,” says Jesus, “I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.” The meaning is clear. Glorification – the fulfillment of Jesus ministry in the world – takes place through his death.

This is the great holy irony of the cross: that this lifting up (from last week’s reading with Moses lifting up the serpent in the desert) is not the lifting up of adulation or power or influence, but on the cross, a place of shame and defeat. And yet this place of shame and defeat, this apparently downward path, leads on to God’s glory and humanity’s redemption, it raises us up.

Jesus’ death on the cross is the ultimate expression of contextualisation, of identification with humanity, with all the pain we inflict on each other and on ourselves. It is also – in this great holy irony – the defeat of the false routes to power in the world and a source of new life and living for all humanity.

And our passage in John makes clear that this is also our path, the path of all disciples, Jews, Greeks, all people who truly want to see and follow Jesus. Are we willing to take this downward path, the path that goes against the grain of all our worldly wisdom?

Of course, there are times when the downward path is forced upon us, when our hopes and dreams collapse or sickness comes, and as all of us grow older and frailer, but there are also times when we must make a choice. Writer Henri Nouwen frequently wrote about the challenge for us, living in a society where upward mobility is the norm, of choosing the ‘downwardly mobile’ path of discipleship. He writes:

Surrounded by so much power, it is very difficult to avoid surrendering to the temptation to seek power like everyone else. But the mystery of our ministry is that we are called to serve not with our power but with our powerlessness. It is through powerlessness that we … form a community with the weak, and thus reveal the healing, guiding, and sustaining mercy of God….As followers of Christ, we are sent into the world naked, vulnerable, and weak, and thus we can reach our fellow human beings in their pain and agony and reveal to them the power of God’s love and empower them with the power of God’s Spirit.

Just as Jesus’ death on the cross is the ultimate expression of contextualisation – so our downward paths of discipleship are our expression of real compassion for each other; our participation in the defeat of the false routes to power and in the new life of the world. In the words of the verse 24, the words the choir just sang for us – When a grain of wheat, into the ground has fallen…this fallen grain will rise to life, this fallen grain will rise to life!

Those words were written by this man, Toyohiko Kagawa, and that quote, “I read in a book that a man called Christ went about doing good. It is very disconcerting to me that I am so easily satisfied with just going about…” is a good quote to summarise his life. Kagawa became a Christian at school in Japan and studied theology at Meiji Gakuin in Tokyo and Kobe Theological Seminary. He was troubled, however, by the focus at seminary on doctrinal correctness rather than an active faith – he often spoke about the parable of the Good Samaritan – and so, in Kobe, he moved into the Shinkawa slum to serve the physical and spiritual needs of the people there. In 1914 he went to the United States to study ways of combating the causes of poverty, and published this work revealing many issues that had been unknown to middle-class Japanese. At Princeton he also read up on agriculture and, on his return, persuaded many Japanese farmers to plant more trees to prevent soil erosion and landslides.

In 1921 and again in 1922 Kagawa was arrested for activities in the labour movement. And while in prison he wrote two novels. Throughout his life he wrote over 150 books. After his release, he helped organize relief work in Tokyo following the 1923 great Kanto earthquake and assisted in bringing about universal adult male suffrage. He organized the Japanese Federation of Labour as well as the National Anti-War League, and continued to evangelize to Japan’s poor, advocate for women’s suffrage and call for a peaceful foreign policy.

In 1940, Kagawa made an apology to the Republic of China for Japan’s occupation and was arrested again. After his release, he went back to the United States in a futile attempt to prevent war between that nation and Japan. His last public duty was as an advisor in the post-war transitional government.

However, Kagawa was not highly regarded in Christian circles in Japan. In his words, “It seemed that everyone was attacking me – the Soviet Communists, the anarchists, the capitalists, the foul-mouthed literary critics, the sensationalist newspaper men, the Buddhists who could not compete with Christ, and those many Christians who profess Christ but believe in a Christianity which is sterile.”

After an incredible life of public service, Kagawa’s recognition faded rapidly after his death, but perhaps like the song he wrote – like the passage it is based on – the grain of wheat that was his life, a life that he modelled as faithfully as he could on the life of Christ, bore much fruit, in Japan and in other places too.

And it is lives like Toyohiko Kagawa’s as well as the paintings we have seen this morning that remind us that in our world, in our own lives, Isaiah’s prophecy is still being fulfilled, “[all] these I will bring to my holy mountain, and make them joyful in my house of prayer; their burnt offerings and their sacrifices will be accepted on my altar; for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples.”

And before we come to sing, I want to show you a final image of this great world-wide community of people who through Jesus’ being lifted on the cross have been drawn to him, this great world-wide community of people who, in their own local communities and in their own ways, are taking the downward path of discipleship; this great world-wide community of God’s people gathered in worship. This is from the 2018 Global Hymn Sing – Jesus shall reign where-er the sun.