Little People – 2 Kings 5:1-14 and Galatians 6:7-16

This is – probably for reasons that are obvious – one of my favourite Old Testament Bible stories, a story where God’s nature breaks through – where the downward compassionate movement of God is revealed – for in this story those who have the potential to be powerful are not the ones in power or the ones wielding power. Rather they are the little people, the low people, the unnamed people, the other people who reveal to us the limitlessness of God’s love.

The passage begins – as you think it should – by introducing the main character first – Naaman; a commander, a great man, a man in high favour, a mighty warrior – and yet Naaman has a (if not fatal than certainly debilitating) flaw; a flaw that makes him so desperate that he listens to the person on the lowest bar of his household social ladder.

She is a slave, captured on one of Naaman’s successful raids into Israel. She is a foreigner. She is a girl. And she is a young girl, a na’arah. But even this word is modified by the adjective, ‘little’ (qatanah). As one commentator explains, “She is a ‘little little girl.'” (Frank Spina) But this little little girl has concern and expresses concern for Naaman and this extraordinary exchange occurs where the great general, the high and mighty Naaman, accepts the advice of a little little girl.

The world then rights itself (almost!) because Naaman goes to the king of Syria who sends him with an official letter to the king of Israel (I say almost because it is a slight comedown for the king of Syria to have to ask a favour of the king of Israel.) But Naaman takes with him appropriate gifts to establish this social relationship – ten talents (500kg) of silver, six thousand shekels of gold, and ten sets of garments – just as if you were to invite the people sitting next to you over for dinner – they would probably in time return the favour. In other words, in return for the great gift of healing me, I present to you all these great gifts.

Now this scene is quite funny. There has been a mix-up. The little little girl’s advice was to go to the prophet, not to the king and to say the king is at a loss is to put it mildly. He is so upset he tears up his clothes! Which would be fine if he could accept the ten sets of garments Naaman has brought, but he can’t because he can’t do what the letter from the king of Syria is asking him to do – he can’t heal Naaman. So – he assumes that this is a political problem that requires a political solution – “Take us to Defcon 3, “he says to his aides. So maybe this is not such a funny scene.

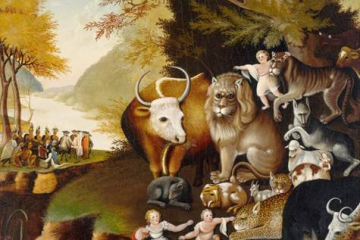

But here again for the second time a little person, a low person, comes to the aid of the great and the prophet Elisha tells the king to send Naaman to him. And so (and this is my favourite scene in the story – for which I cannot find an appropriate image so we are all going to have to picture it in our minds) the great general, the high and mighty Naaman, with his ten talents (500kg) of silver, six thousand shekels of gold, and ten sets of garments, with all his horses and chariots, and his servants, pulls up outside Elisha’s small mud brick house. And the prophet doesn’t even come out of the house!

And Naaman is furious! I thought that for me – for me! – he would surely come out, and stand and call on the name of the Lord his God, and would wave his hand over the spot, and cure the leprosy!Wash in the Jordan! Name any river in Damascus. Isn’t it better than all the water in Israel!

But for the third time the little people save the day. Naaman’s servants say to him, “Father, if the prophet had commanded you to do something difficult, would you not have done it? How much more, when all he said to you was, ‘Wash, and be clean’?” The words here are actually ‘a great thing’ (dabar gadol). If you were asked to a great thing you would do it, why not do this little thing? And persuaded by these unnamed people Naaman does‘according to the word of the man of God’, does the little thing, immerses himself seven times in the Jordan, and his flesh is restored like the flesh of a young boy. We cannot miss the irony that the great man through the intercession of the little girl and the little man and the little people is made like a little boy. Naaman humbles himself and, if we read on to verse 15, becomes a child of God.

But there is a fourth example in this story – of the downward and outward compassion of God – and that is Naaman himself. Many years later he pops up in a sermon – preached in a synagogue in Nazareth – a sermon delivered by Jesus himself – a sermon we keep referring back to – where Jesus makes the very unpopular point that Naaman is included in the blessing of God, embraced by the compassion of God, fully immersed in the limitless love of God even though he is unclean, the sufferer of a dreaded skin disease, and a foreigner, outside of God’s covenant with God’s people.

“No outcasts,” writes Garry Wills in What Jesus Meant, “were cast out far enough in Jesus’ world to make him shun them — not Roman collaborators, not lepers, not prostitutes, not the crazed, not the possessed. Are there people now who could possibly be outside his encompassing love?”

Each of these little ones – the little little girl, the low prophet, the unnamed servants and the foreign unclean other Naaman reveal to us the scope of God’s compassion and the downward trajectory of God. For God, revealed to us in Jesus, rather than striving for a higher position, more power and more influence, moves, as Karl Barth says from “the heights to the depth, from victory to defeat, from riches to poverty, from triumph to suffering, from life to death”.

This movement – this free movement made in love – is a mystery to us. We cannot understand how we are rescued by one who is powerless, strengthened by one who has made himself weak, led by one who comes to us as a servant. We cannot grasp why someone would give up so much to be completely present in our lives. And yet, in the world of Henri Nouwen: Jesus’ whole life and mission involve accepting powerlessness and revealing in this powerlessness the limitlessness of God’s love. Here we see what compassion means. It is not a bending toward the underprivileged from a privileged position…On the contrary, compassion means going directly to those people and places where suffering is most acute and building a home there.

And we are called too to participate in this downward movement of compassion – to reject the games played by power to make our home with those the world thinks of as little because we are all God’s children.

I was also reminded thinking about this of the story of this church’s engagement with Aboriginal reconciliation, of the apology made to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on 10th Nov, 1997, and the plaque that was dedicated in 2013 acknowledging the traditional owners and spiritual custodians of the land on which we meet, and that we, as a church, have committed ourselves “to seek greater understanding of the difficulties, needs, and aspirations of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities, and to support the process of a just reconciliation.” I have also been reminded of the personal connections and their impact. Aunty Agnes Shea, who was here at the unveiling, tells the story that it was Thorwald who first encouraged her to speak in front of people and now she speaks widely, welcoming people to Ngunnawal country.

As we begin a new parliamentary term in this country, I wonder to what extent our politicians will demonstrate this downward compassionate way of love that is the compassion of God… But I also wonder to what extent our churches can demonstrate that rather than desiring position and position and covering up the sins of our past, we genuinely embody the compassion of God… And day by day I continue to wrestle with my own desire to wield power and influence – in some small way – rather than follow Jesus, to take his downward trajectory of love, and I hope that you do as well; that together we can be a community building a home that welcomes all God’s children.